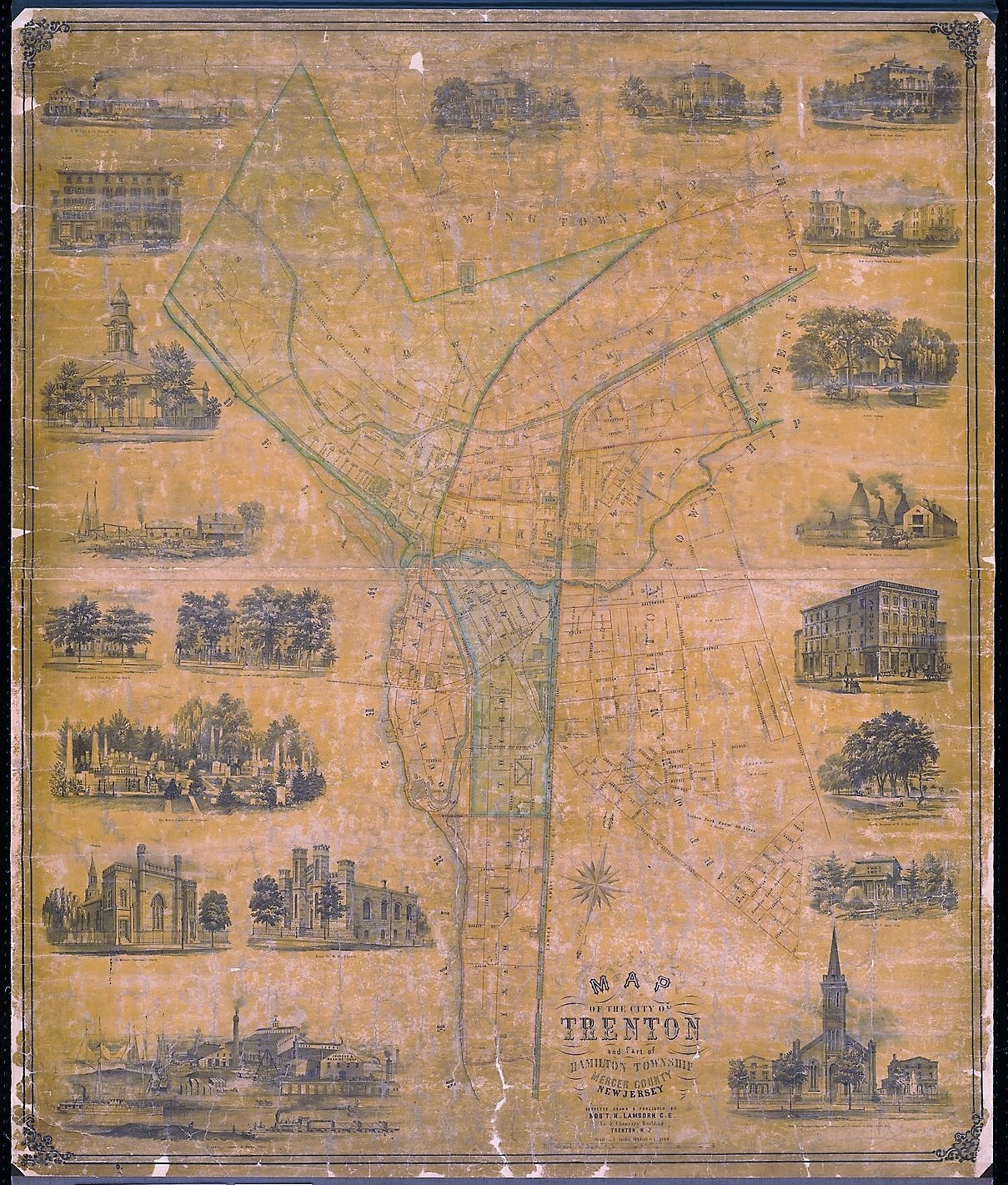

The growth and decline of entrepreneurship in Trenton, New Jersey, 1850-1930

David Singerman

In 1850, Trenton was a small city, but by the 1880s it had become a leading industrial center for iron, rubber, machine tools, and ceramics. Among its potters in particular, Trenton developed a strong culture of entrepreneurship. But such entrepreneurship was based on skilled labor and civic-minded capitalism, and by the early 20th century the city’s businesses could not keep pace. In 1890, Trenton was the 50th largest city in the country, but after the depression of 1893 the city never recovered the rapid growth of earlier decades, and by the 1920s its factories had already begun to shutter.

A historical study of Trenton’s rise and fall offers the chance to understand thriving entrepreneurial culture in a dramatically different context from today’s emphasis on computers and biotechnology. Looking at Trenton almost a century after its decline, we can better understand what small-to-medium-sized cities can do to encourage new and growing businesses more generally—and how to gauge the success of those efforts in the face of adverse macroeconomic circumstances.

Industries

Pottery. In 1850 few porcelain or earthenware products were made in the United States; most were imported from England, particularly from Staffordshire. The initial entrepreneurs for Trenton’s pottery industry were midcentury English immigrants, drawn by local mineral deposits, ample water power from the Delaware, and the city’s proximity to larger markets in Philadelphia and New York. By the 1890s Trenton boasted dozens of potteries employing over 4,000 workers.

Iron and steel. Even before pottery, ironmaking had been Trenton’s chief industrial product, drawing on coal from eastern Pennsylvania and iron from northwestern New Jersey. The Trenton Iron Works in 1857 made the first wrought-iron beams in the country, which still support New York’s Cooper Union, the U.S. Capitol, and the U.S. Treasury. By the end of the century Trenton was also home to 18 machine works that employed 4000 people.

Rubber. By 1923, employment in pottery in Trenton had leveled off below 4500, but rubber employed more than 8000 people, and the city’s output was second only to the rubber capital of Akron. Part of the city’s advantage came from its strength in pottery: in chemical and processing terms, rubber resembled ceramics enough that supporting industries like machine-making and craft tools could adapt.

Decline

Trenton’s entrepreneurial culture in pottery depended on strong local social networks. The industrialists who controlled Trenton’s financial and civic institutions operated the former to provide low-cost capital to pottery entrepreneurs, while the latter functioned to circulate market and technological information. An entrepreneur needed access to these elite networks—but he also needed a deep understanding of the ties that bound the city’s skilled craftsmen, since making pottery took dozens of different types of artisans.

In the 19th century, in Trenton’s industries as in others, entrepreneurs were largely craftsmen or foremen—skilled workers who acquired enough knowledge of bookkeeping and accounting to start and manage a business on their own. But the more national and competitive marketplace of the 20th century demanded skills that these entrepreneurs didn’t possess. Nor could they afford the specialized engineers and managers who would implement “scientific management,” root out inefficiencies, and cut costs by stripping workers of their control.

Meanwhile, the cooperation between labor and employers—a “mutuality of interests” that had sustained Trenton’s industries—also crumbled in the face of national competition. Enterprises further west were larger, and with less-powerful labor unions they were free to mechanize production. The machine tool industry was crippled by strikes, though in pottery cooperation lasted until the 1920s. But just as manufacturers asked workers for wage cuts to remain competitive, and as they pushed to mechanize the skilled elements of production, the cost of living was on the rise. Facing bleak prospects as independent firms, many of Trenton’s pottery companies sold themselves to nationwide concerns before 1930.

Future research

Previous studies of Trenton have mostly examined it from the perspectives of economic, social, and labor history. At the risk of anachronism, what can we learn from studying Trentonians’ entrepreneurship—how they started companies and guided them to stability? And what, if anything, made Trenton’s entrepreneurship distinctive for much of the late nineteenth century? To answer these questions, future CIT.ee work on Trenton will draw on archival, visual, and statistical sources.

References

- John T. Cumbler, A Social History of Economic Decline: Business, Politics, and Work in Trenton (Rutgers, 1989)

- Marc Jeffrey Stern, The Pottery Industry of Trenton: A Skilled Trade in Transition, 1850-1929 (Rutgers, 1994)